Patients Playbook | Recovery Tools: The Do Goods vs the Feel Goods (vs the Do Harms)

A Clinician’s Guide to Smarter Recovery Choices

Recovery is a lot like driving at your top speed — you can’t force it faster, but you can remove the barriers.

Some tools help. Some just feel nice. Some cause real problems. Here’s how to tell them apart.

This is a no-paywall blog post with insights I believe are valuable. If you find it useful, subscribe to my Substack for more in-depth content, exclusive case studies, and clinical insights.

Your support helps me continue sharing everything I’ve learned in the clinic with the world

☕ Prefer a one-off thank you? Buy Me a Coffee.

This post is a guide only and should not be taken as medical advice. It does not replace assessment and recommendations from a registered and regulated healthcare professional.

Working in this job, I get asked a lot about recovery gadgets, hacks, and therapies. Things like compression pants, ice baths. massage guns, cupping, dry needling.

\Which ones actually help? Which ones just make you feel better? And which ones could do more harm than good?

This Patients Playbook post breaks down the difference between:

the Do Goods,

the Feel Goods,

and the Do Harms

and how you can make smarter recovery choices without wasting your time, money, or energy.

The Car Analogy: How Recovery Actually Works

Think of recovery like driving 100km at your car's top speed.

For a younger athlete, maybe the top speed is still 100km/h.

For a seasoned veteran, it might be 95km/h.

For someone managing old injuries, maybe 90km/h.

You cannot drive faster than your engine's true capacity.

What you can do is:

Pump the tyres.

Close the windows.

Remove headwinds.

Fill the tank with premium fuel.

These steps don't make you drive faster. They help you maintain your true top speed without breakdowns.

Painting the car a fancy colour? Adding neon lights? That's just cosmetic.

It doesn't make you go faster. It might even slow you down.

And this is recovery.

We recover from sports, exercise, and injuries in a set time. We cannot speed it up.

We can only facilitate it, support it, and ensure we don't do anything that slows it down.

Big Recovery Tool brands have even been in legal trouble for making claims that they can accelerate healing or increase strength and power — claims that don't hold up (example: RockTape lawsuit).

Recovery progress is like hitting your top speed (100km/h) and reaching your destination at the right time (after one hour).

As we age, unfortunately, our healing rate naturally slows a little — maybe our top speed becomes 90km/h — and it might take a little longer to reach the destination.

And that's okay — as long as we support the journey, not sabotage it.

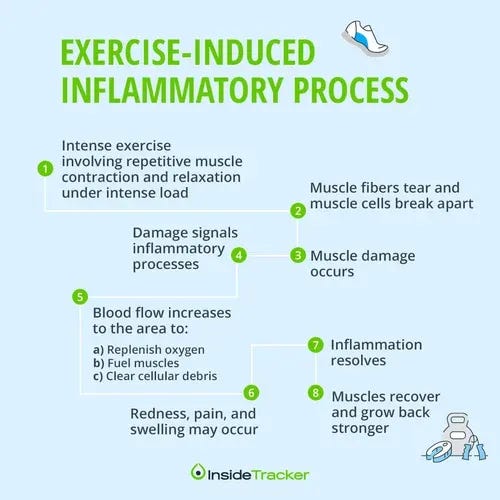

It's also important to remember: acute inflammation following sports or exercise is GOOD.

It's the body's natural way of clearing out the by-products of micro-injury, repairing tissues, and laying the groundwork for positive adaptations — whether that's improving the aerobic and anaerobic capacity of your muscles, or increasing muscle size.

Suppressing this inflammation too aggressively (like with excessive ice baths or anti-inflammatories) can blunt these important processes.

The Big Ticket Do Goods

The true heavy hitters of recovery aren't glamorous.

They don't get you social media likes.

But they work.

Sleep: Still undefeated as the #1 recovery tool.

Hydration: Your tissues are living, fluid-filled systems.

Nutrition: Building blocks for repair and fuel.

Load Management: Smart programming prevents breakdowns before they happen.

If you're ignoring these and buying $400 compression boots, you're putting mag wheels on a car with a leaking engine.

The Feel Goods (and the Potential Do Harms)

Some tools just feel good.

They don't meaningfully speed up recovery.

They can be fine — but they can also cross into harmful territory if misused.

Regular readers will know the Feel Goods already — they're the itch scratchers.

They offer temporary relief, but too much scratching can cause problems.

Get the Do Goods sorted properly, and you'll have less itch to begin with.

Massage can feel fantastic — but aggressive deep tissue work can damage healing tissues.

Ice baths can help reduce acute inflammation — but if used after strength training, they can blunt muscle adaptation.

Compression pants might feel snug and supportive — but they aren't changing tissue recovery rates.

Important Caveat: I Support Feel Goods

Before we go further, let's be clear:

I support Feel Goods.

Everyone deserves to feel good.

In clinic, manual therapy can temporarily reduce pain — opening a window for better rehabilitation.

In sport, a Feel Good can assist mental, psychological, and emotional recovery.

If a Feel Good helps an athlete sleep better, recover mentally, or simply feel ready — then it can indirectly enhance one of the Big Ticket Do Goods like sleep.

The key is knowing what it is (and what it isn't). But there’s also a cost associated to some of these Feel Goods that makes you reconsider their value.

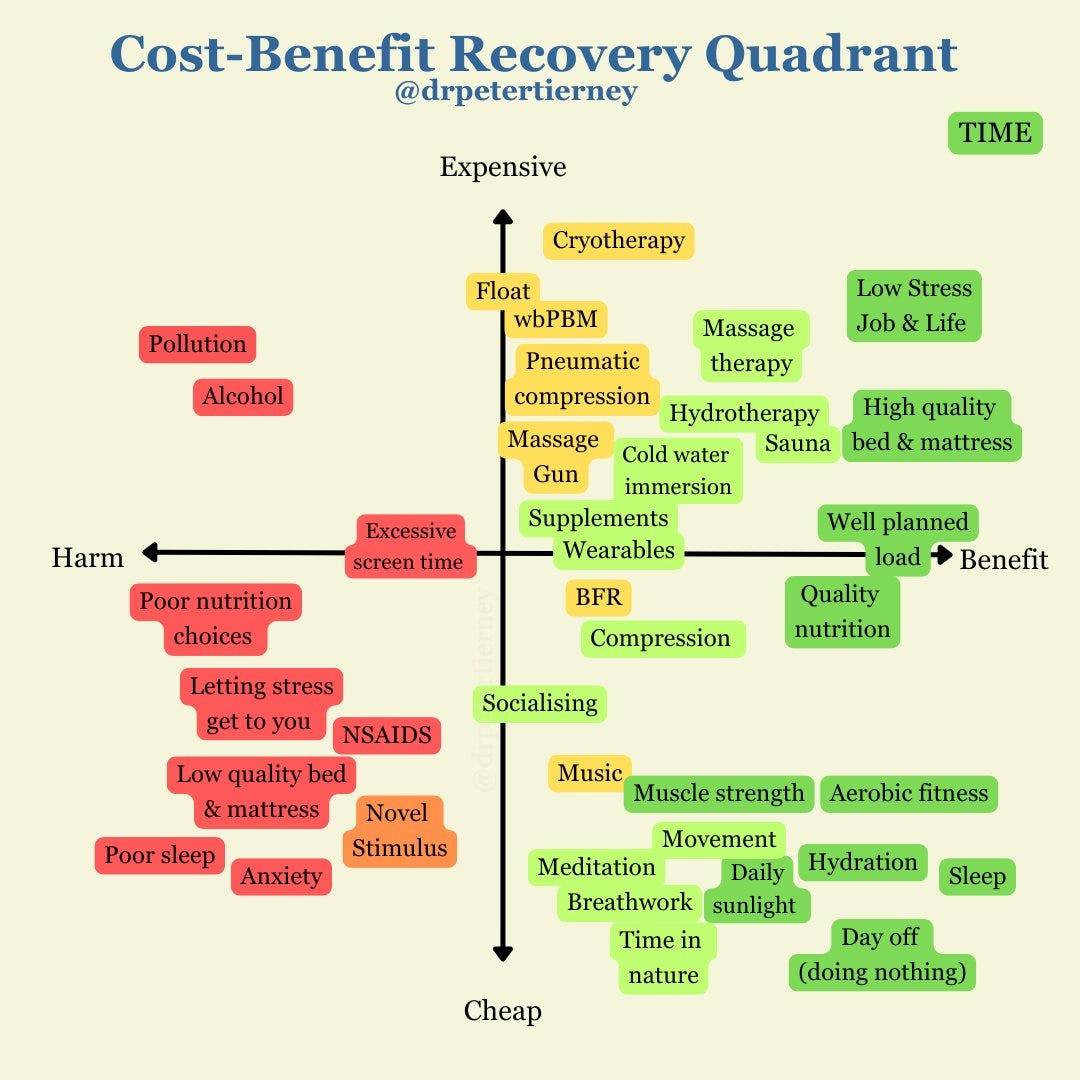

Here’s a Recovery Quadrant by Dr Peter Tierney that demonstrates that:

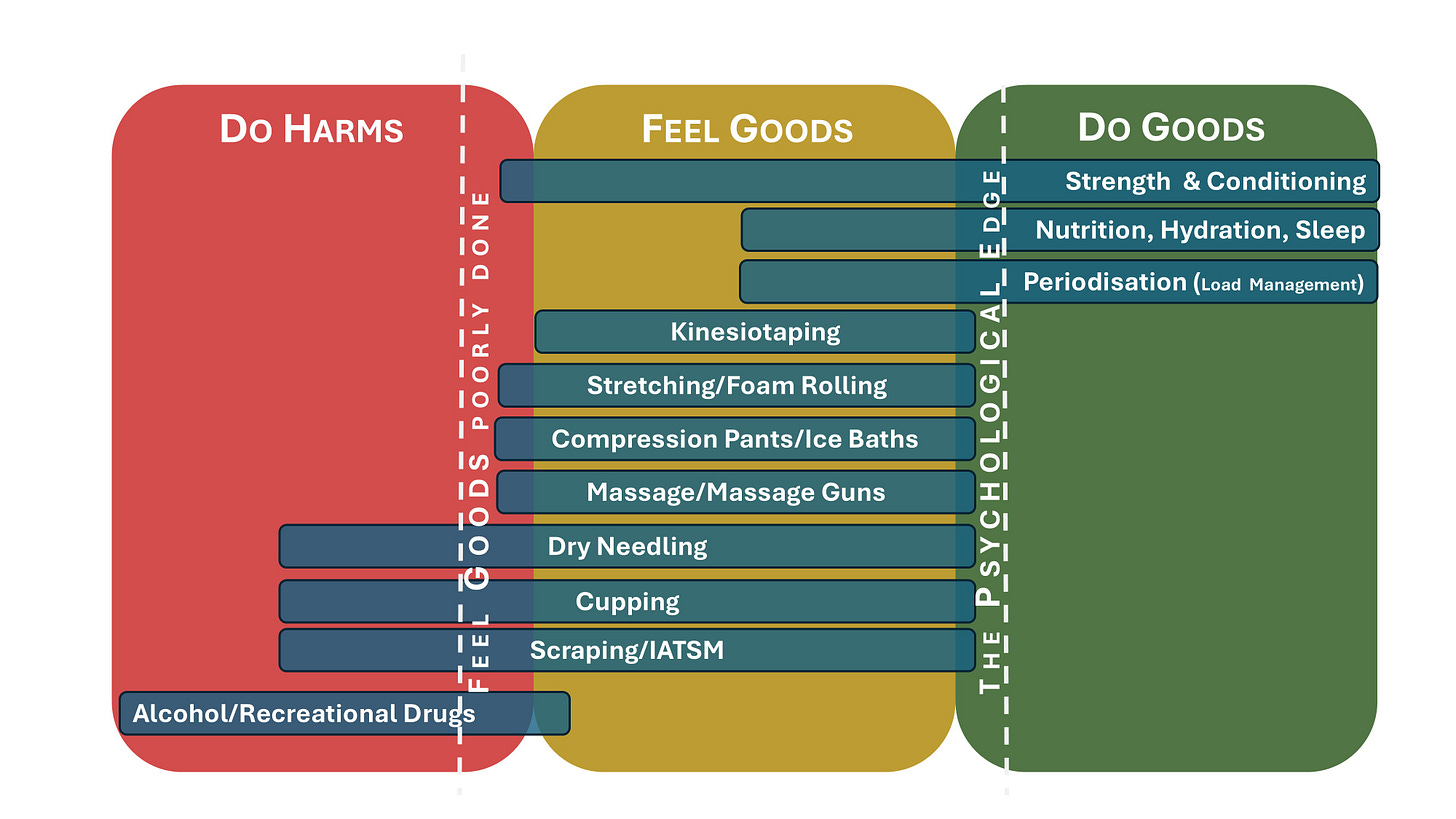

However, in my mind it tends to work this way for the common stuff my patients are exposed to in life and on the internet:

There are clear evidence-based Do Goods. I’ve discussed these in greater depth here:

These are scientifically proven to reduce injuries and improve performance (Do Good). However even S&C done poorly (inappropriate Gym loading leading to injury) can Do Harm. So it falls down to the competence and experience of the provider.

Then there’s the Feel Goods. Advocates will cherry pick the studies that suit their narrative here, but the majority of them, at best, provide a psychological edge only, at worst: don't do much at all (thus the white line on the left side of the Do Goods section). They just “Feel Good”. Makes sense, right?

However, some of the Feel Goods — if done poorly, or provided by someone less competent or less experienced — can Do Harm. So there’s some risk there.

Some, purely by design, cause harm in order to create noise in the system so the patient doesn’t hear the other noise (pain/discomfort) for a short time.

Some people (often athletes) are wired to crave that “GO HARDER, STICK YOUR ELBOW IN IT!” experience. It’s almost a form of pain-as-proof logic — where intensity is mistaken for effectiveness. It helps them “feel good” psychologically, even if it’s not doing good physiologically. That’s how some of these slide into the Feel Good zone.

But here’s the test: If this same treatment were delivered in a dark alleyway by a stranger, would it still feel like recovery? Or would we call it what it really is — someone causing tissue damage, ruptured capillaries, and bruising… and selling it as care?

And then there’s the clear Do Harms: Most of us know about them already. Recreational drugs, alcohol, smoking, poor sleep, etc.

Then there’s the Feel Goods. Advocates will cherry pick the studies that suit their narrative here, but the majority of them provide a psychological edge only (thus the white line on the left side of the Do Goods section. They Feel Good. Makes sense right?

However, some of them, if done poorly, or provided by someone less competent or less experienced, they can Do Harm. So there’s some risk there. Some, purely by design cause harm, in order to create noise in the system so the patient doesn’t hear the other noise (pain/discomfort) for a short time.

Some people (often athletes) are wired to crave that “GO HARDER, STICK YOUR ELBOW IN IT!” experience. It’s a classic example of pain-as-proof — the belief that if it hurts, it must be helping. That belief can make someone feel good, even when it’s not doing good from a scientific perspective.

But here’s a useful test:

If this same intervention were delivered to you in a dark alley by someone you didn’t know — against your will — would it still feel like recovery?

Or would you call it what it really is: tissue damage, ruptured capillaries, and bruising?

This is where Contextual Effects come in — essentially, the White Coat Effect.

"Approximately half of the overall treatment effect in RCTs seems attributable to contextual effects rather than to the specific effect of treatments." https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34311793/

The same treatment, delivered in the same way, to the same person, can produce a different outcome based on the environment:

A football locker room vs a calm, candle-lit clinic

A guy in a hoodie vs someone in a white coat or polo

$20 in a shopping centre vs $150 in a sports medicine clinic

The effect isn’t just in the hands — it’s in the setting, the story, and the perceived status.

That’s not nothing. But it’s not science either.

And then there’s the clear Do Harms: Most of us know about them already. Recreational Drugs, Alcohol, Smoking, Poor Sleep etc.

Even some of those might fall in the Feel Good in adequate quantities but generally, they’re are poo-poo’d by Sports Science for good reasons.

Cupping: The Psychology of "Visible Recovery"

We've all seen Olympians covered in giant purple cupping marks.

What it really signals:

It telegraphs weakness.

You’re advertising to opponents: “I'm hurting.”It creates a psychological crutch.

If you lose, the bruises offer an excuse: “See! I was injured!”It misleads the public.

If you win, people wrongly assume: “Cupping must have helped! I need cupping too!”

No. No you do not.

Nobody needs cupping.

Just like nobody needs a hickey to recover faster.

"If bruises were the secret to Olympic gold, I'd have just sent myself down a flight of stairs before every tournament."

Cupping ruptures blood vessels — it doesn't "release toxins."

It just creates a louder signal in the body to distract from the original one.

And it can harm the vascular supply tissues need to heal.

Lessons from Elite Sport

Working with the best athletes in the world taught me something important:

At the very top, feeling good matters.

Sometimes, chasing a tiny psychological edge — a 1 percent-er — is worth it.

But as a wise mentor once told me:

“Spending your time and money on a bunch of 1%ers is still 1%. They don’t add up.”

Another lesson? The public often falls for the Fallacy of Authority:

“If elite athletes use this, it must work.”

But success doesn’t validate the method. The perceived authority or achievement of the athlete is used as evidence — without any actual scientific proof.

Even G.O.A.T.s believe some pseudoscientific nonsense.

Remember Power Balance bands?

Dozens of athletes wore them. Swore by them.

One of the shortest-lived pseudoscience fads in sports history — and a perfect example of what not to copy.

In elite sport:

Feel Goods are used strategically.

They're delivered by highly trained professionals.

They never replace the Big Ticket Do Goods.

What works for Novak Djokovic or Simone Biles in a Grand Slam is not necessary for:

Sub-elites

Juniors

Weekend warriors

Average Joes and Janes

Don't sprint out to buy air compression pants just yet.

Fix your sleep first.

But if you have cash to splash on 1 percent-ers and you’ve completed the rest of the 99 percent-ers, then go for it.

Choose Your Recovery Wisely

Recovery is a simple game made complicated by shortcuts.

Your first priority:

Sleep.

Nutrition.

Hydration.

Load management.

Your second priority:

Smart, strategic use of Feel Goods — for psychological benefit, not as a crutch.

Your third priority:

Avoiding anything that causes harm in the name of "feeling better."

And remember:

Do enough Do Goods, and you won't need as many Feel Goods — you'll already feel good.

"Your best recovery tools aren't bought on Instagram. They're built with patience, good decisions, and common sense."

Stay smart. Stay skeptical. Stay healthy.

Final Thought: Get Your Advice from Experts

When it comes to recovery, don’t just follow whoever’s loudest online.

Get your advice from true experts:

Nutrition: Accredited Sports Dietitians

Injury Management and Prevention: Physiotherapists, Strength and Conditioning Coaches, Sports and Exercise Medicine Physicians

Medical Issues: Sports and Exercise Medicine Physicians

Feet and Biomechanics: Sports Podiatrists

Psychological Recovery: Sports Psychologists

They’re trained, regulated, and experienced.

They’re the ones who can guide you toward real recovery — not just temporary distractions.

Did you find this valuable? If so, even a small contribution helps me keep content like this going.

This is high-value information that normally costs hundreds of dollars in a clinic—here, you get it for free.

☕ Buy Me a Coffee to say thanks, or become a paid subscriber and get subscriber-perks such as asking me about anything Musculoskeletal pain and injury in the Substack chat.

Tailor your Nick Ilic | Physio Clinician subscription:

You can customise which topics you receive updates for by selecting 'Manage Subscription' in your Substack options (in your browser), or by clicking 'unsubscribe' at the bottom of any email—don’t worry, it won’t unsubscribe you immediately! You'll then be able to choose your preferred sections:

✅ Patient Playbook

✅ Clinician’s Corner

✅ Research Reviews

✅ Clinician’s Compass

Choose what suits you best—I promise I won’t take it personally!