This is a no-paywall blog post with insights I believe are valuable. If you find it useful, subscribe to my Substack for more in-depth content, exclusive case studies, and clinical insights.

Your support helps me continue sharing everything I’ve learned in the clinic with the world.

☕ Prefer a one-off thank you? Buy Me a Coffee.

This post is a guide only and should not be taken as medical advice. It does not replace assessment and recommendations from a registered and regulated healthcare professional.

There’s a common mistake many clinicians make early in their tendon-rehab journey—assuming all tendons behave the same.

They don’t.

We can’t keep copy-pasting lower limb protocols into upper limb presentations and expecting things to just "work." This is a nuanced game—one where understanding the job description of the tendon in question matters as much as the load dose itself.

I’ve seen the tendon bandwagons come and go:

The Eccentrics fix all the Tendons phase.

The Isometrics fix all the Tendons phase.

The Isometrics then Heavy Slow Isotonics then Eccentrics then Plyometrics - fix all the Tendons phase.

This blog explores the key clinical differences between lower limb and upper limb tendons, why we treat them differently, and how failing to recognise the distinction can derail your rehab approach before it even begins.

Lower Limb Tendons: Load-Tolerant, Load-Thirsty

Think of the lower limb classics: the Achilles and Patellar Tendons.

Patellar tendons go vertical. Achilles tendons go horizontal.

Different angles, same story:

These are tendons that are designed to absorb and transmit massive loads, often on a daily basis. They thrive on load—so long as it’s progressive, measured, and dosed correctly.

They’re used to dealing with:

Ground reaction forces from running, landing, and changing direction

Rapid stretch–shortening cycles

Bodyweight multiplied several times over during dynamic movement

In most cases, we’re dealing with tendons that respond predictably to:

Heavy Resistance (Heavy Isometric and Isotonic gym tasks. And let’s be clear: "Heavy Resistance" isn't a blue resistance band. We're talking 1.5 to 3 times body weight in some instances.)

Progressive energy storage and release work

Clearly defined return-to-sport markers (e.g. hop tests, SL calf raises, etc.)

Pain during loading is often permissible—if it’s controlled. We have enough data and clinical experience to guide patients through tolerable pain with confidence. “Some pain is okay” is a phrase that holds weight in lower limb rehab. In fact, sometimes it’s essential to get the job done.

Please…. if you think a patient in front of you has Patella Tendinopathy and they aren’t an elite jumping athlete, make sure you rule out other differential diagnoses as this rarely occurs in other cohorts and is commonly misdiagnosed.

Not All Tendons Are Built for Bounce

Here’s a useful lens I’ve found helpful—and clinically clarifying:

Some tendons are Springs. Some are Stabilising Straps.

That’s not textbook terminology, but it holds up well in practice. More formally:

Stretch–Shortening Cycle (SSC) tendons are built to absorb load, store it, and release it.

Think Achilles, Patellar, and yes—even the Common Wrist Flexors when acting as prime movers.

These tendons are built for propulsion. They behave like biological springs—compressing, recoiling, and repeating with each movement cycle.Then we have Positional (or Postural) Tendons—the ones that exist to stabilise and optimise joint positioning.

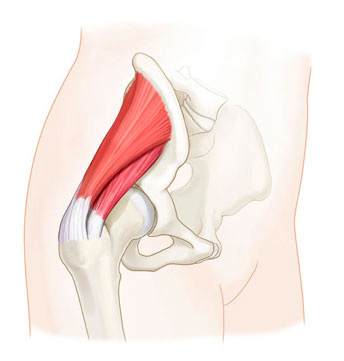

Think Gluteal tendons, Common Wrist Extensors, and the Rotator Cuff.

Their job isn’t force production—it’s coordination, precision, and positional control.

This distinction fundamentally changes our rehab approach.

With SSC tendons, we’re building up tolerance to load and stretch—encouraging them to store and release energy efficiently.

With positional tendons, we’re often trying to reduce sustained compression, improve joint mechanics, and retrain how the tendon holds its post while the limb moves around it.

That’s why most of us no longer prescribe loaded wrist extensions for lateral elbow pain. Instead, we favour positional exercises—like holding a weight in a specific wrist position while moving the shoulder or elbow through functional tasks. The tendon doesn’t need concentric overload. It needs support. Coordination. Re-integration.

These Tendons Tell Bigger Stories

What’s even more interesting—and clinically revealing—is that it’s often these positional tendons and complexes that act as barometers for the system.

They’re the ones that don’t just get grumpy from a heavy lift or a long day on the tools.

They become painful, stiff, and stubborn when the system itself is under pressure.

Think:

Middle-aged patients with subacromial pain that lingers for months

Chronic lateral elbow pain that came on “out of nowhere”

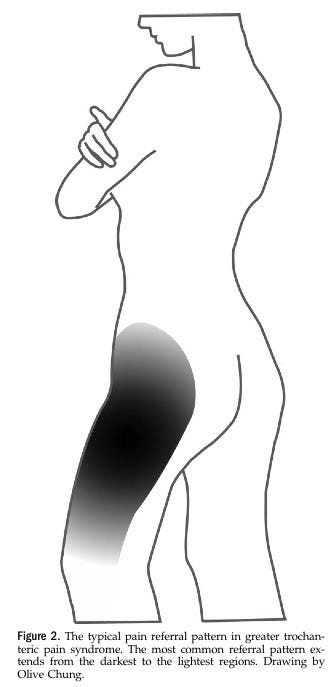

Bilateral gluteal tendinopathy in someone with central adiposity and poor sleep

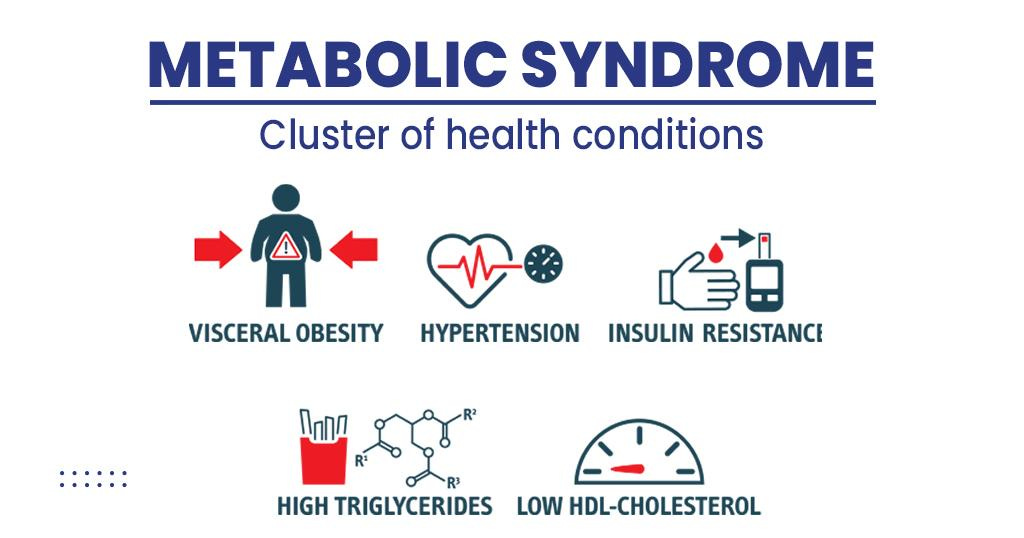

There’s often a metabolic backdrop here—insulin resistance, altered lipid profiles, low-grade systemic inflammation.

In women aged 50–60, menopause is another key player—bringing a reduction in collagen turnover and tendon healing capacity. This is a particularly common story in gluteal tendinopathy.

These tendons may not be failing due to excessive load… they’re failing to adapt because the systemic environment is hostile to repair.

Yes, sometimes these issues follow a clear overload event. A weekend gardening blitz. A sudden increase in tennis.

But more often, these are the tendons that take 6–12 months to settle—regardless of how evidence-based your exercise prescription is.

Check out the below Tennis Elbow update on how that plays out:

These cases require a broader rehab lens.

Rehab becomes less about tendinous capacity, and more about physiological readiness.

Less about sets and reps. More about managing the load above the neck and below the skin.

Upper Limb Tendons: Smaller, Fussier, and Far Less Forgiving

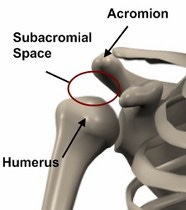

Enter the world of lateral elbow pain and rotator cuff overload—transitional tendons that sit somewhere between the worlds of load and control.

Let’s take the ECRB, the main driver of tennis elbow.

Unlike the Achilles, ECRB’s job isn’t propulsion. It’s postural—to hold the wrist stable during grip, type, lift, or repetitive fine motor tasks. It doesn’t love big concentric/eccentric cycles. It loves control.

And therein lies the difference. These tendons:

Fail under compression far more often

Live in low-load environments and then get overloaded by task repetition, awkward postures, or sudden demands (hello, first-time house painter with a roller)

Applying HSR to these tendons without thought leads to trouble. They often don’t tolerate pain. And the same tendon that flares with a TheraBand can be doing 8,000 reps of typing at work the same day.

Compression Is the Variable That Changes the Game

In lower limb rehab, we often embrace compressive positions in mid-late stage rehab.

Heel drop with dorsiflexion? Absolutely—perhaps not immediately, but inevitably.

Gluteal loading in deep hip flexion? Bring it on.

But upper limb tendons don’t play the same game.

The radial head compresses the sensitised ECRB tendon when gripping in elbow extension and forearm pronation.

The sensitised rotator cuff complex gets compressed in the sub-acromial space (which is their normal Monday-to-Friday job—but sometimes the sub-acromial space just needs a weekend or a two-week getaway).

The proximal hamstring tendon (Runner’s Bum) gets compressed during hip flexion or by external surfaces like hard seating. Common in runners, deadlifters, and yoga practitioners, this tendon suffers a double-whammy of internal and external compression. It is especially prone to overload in middle-aged adults—particularly women in menopause—when stretching, sitting, or performing repetitive deep flexion activities. Rehab here means reducing compression, avoiding aggravating positions, and gradually reintroducing load via knee-dominant hamstring tasks before progressing to hip-dominant loading in neutral, then flexed positions.

For these tendons, we often start by loading them out of compression (for Runners Bum, leg curls instead of hip hinges for example), then gradually build tolerance to loading into compressive positions. Ironically, those compressive positions are often the most efficient at generating force—calf raises in dorsiflexion being a perfect example. But we must earn the right to train there. It’s a phase-based approach, not a default starting point.

And sometimes, tendon overload is secondary—a result of something else in the kinetic chain breaking down.

Take the Achilles, for example. An older athlete might develop Achilles tendinopathy after a soleus injury. If the soleus fails to recover its force output, the Achilles can become overloaded by picking up the slack.

This is why we must assess surrounding muscle-tendon units—not just the sore spot.

Use dynamometry to confirm and quantify pain-free force production deficits, not guess them.

Clinical Takeaways

Here’s what we need to carry forward into our practice:

Respect the difference in tendon purpose. ECRB ≠ Achilles. Rotator cuff ≠ patellar tendon. Function matters.

Compression of sensitive tissues is often the villain in upper limb tendon pain. Load type (eg: positional) matters as much as load amount.

Pain tolerance thresholds differ. “Push through a bit of pain” might help an achilles tendon —might flare a shoulder or gluteal tendon for a week.

Sometimes it’s not the tendon—it’s a weak neighbour. Test it properly.

Systemic load matters. Especially when rehab stalls, zoom out before doubling down.

Final Thoughts

Tendons are beautiful in their simplicity—until they aren’t.

In the lower limb, we often get away with cookie-cutter rehab plans. In the upper limb, we need nuance, patience, and a broader lens. The evidence base is catching up, but the clinical complexity has always been there.

So next time you catch yourself programming a wrist extensor the same way you’d load a quad, take a breath, pause, and ask:

What’s this tendon actually trying to tell me?

Sometimes, the answer isn’t in the sets and reps.

Sometimes, it’s in the story.

I highly Recommend Peter Malliaris’ Tendinopathy Rehab Coursework.

https://www.tendinopathyrehab.com/

Peter’s modern frameworks address the complexity in rehabilitating different tendinopathies. Below is a pic from his Website Blog.

If this post helped you rethink an approach, refine a diagnosis, or improve patient outcomes, consider supporting my work.

☕ Buy Me a Coffee to say thanks, or become a paid subscriber—healthcare providers who subscribe can share cases with me or ask clinical questions anytime.

Tailor your Nick Ilic | Physio Clinician subscription:

You can customise which topics you receive updates for by selecting 'Manage Subscription' in your Substack options (in your browser), or by clicking 'unsubscribe' at the bottom of any email—don’t worry, it won’t unsubscribe you immediately! You'll then be able to choose your preferred sections:

✅ Patient Playbook

✅ Clinician’s Corner

✅ Research Reviews

✅ Clinician’s Compass

Choose what suits you best—I promise I won’t take it personally!